“Now, shoot a video or a photo… It’s easy. Add a filter, and that’s it,” she said with a laugh, looking at me, totally confused.

I still remember it clearly - it was 2013, and I was sitting with a group of young people when they urged me to try Snapchat. I downloaded the app before but never really used it, so I opened it, and suddenly… the camera was on. No menu. No feed. Just the lens, ready to shoot.

I froze.

What was I supposed to do?

What I knew was that you open an app, choose an action, then maybe take a photo. But Snapchat skipped the choosing. It opened straight into doing.

It took me a while to realize that this wasn’t a mistake. It was the intention.

Evan Spiegel, Snapchat’s founder, saw a different rhythm of interaction – one rooted in the immediacy of creation. He understood that for a generation raised on smartphones, expression starts with the camera, not the keyboard. He saw what others hadn’t yet noticed.

He drew what he saw.

I was reminded of that moment recently while visiting Ruth Asawa: Retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Art (on view through September 2, 2025). It’s the kind of exhibition that, if you pay close attention, offers surprising lessons for business leadership.

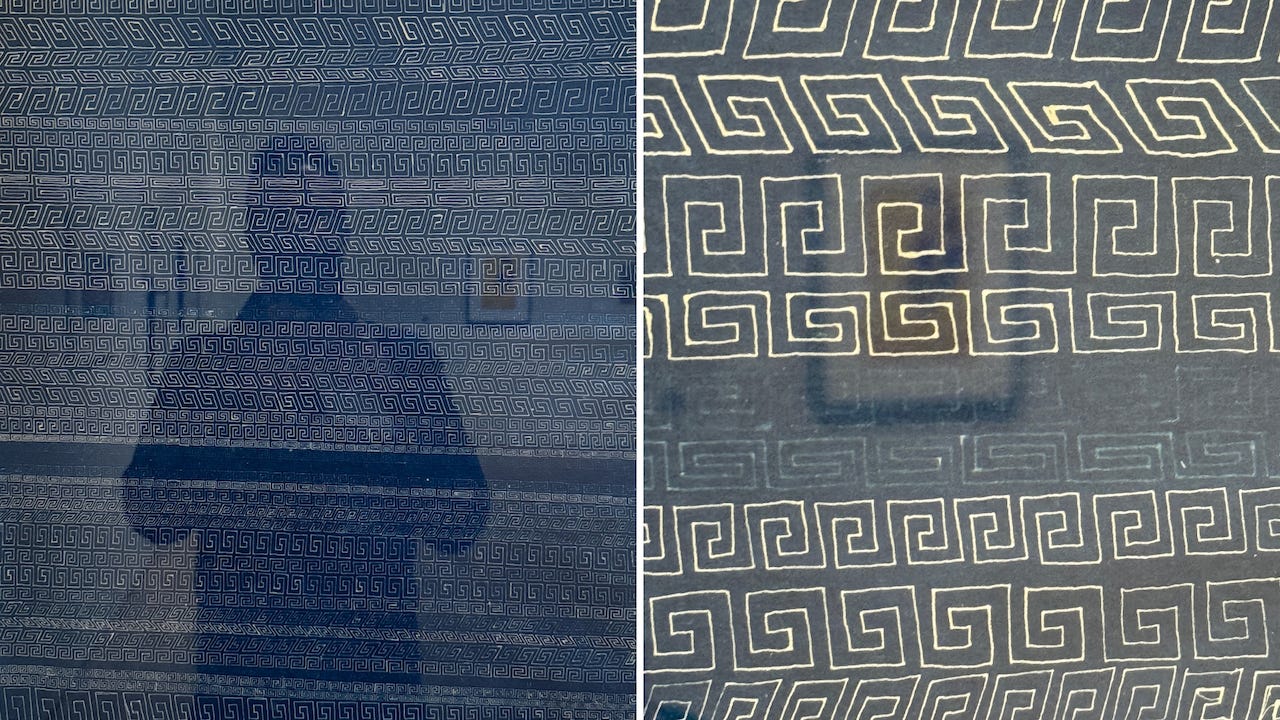

In one of the galleries, a wall of Greek meander patterns caught my eye – looping lines stacked in rows. Some looked bigger, some smaller, some slightly off-center. At first glance, they seemed like repetitive exercises. But the wall text revealed their origin: a training in perception from Josef Albers’s design course at Black Mountain College. What seemed like a simple pattern was actually a test in how to see – not how to copy. It was a training in perception.

Students were taught to repeat the pattern again and again, not to create something new – but to unlearn. To see line, shape, and space without assumptions.

Albers used to say:

“Draw what you see, not what you know.”

What he meant is that our knowledge – our assumptions, training, expertise – can become a kind of blindness. We stop looking because we believe we already understand. But seeing is a discipline. It takes effort, restraint, humility. And in business, as in art, that kind of seeing is often the source of innovation.

The Twitch of Certainty

There’s a moment I’ve witnessed time and again before my keynotes. Someone in the audience – usually a seasoned professional – leans over and whispers, “Art in business? Seriously? What do artists know about leadership? They just take a siesta and draw.” 😉

It’s said with a smirk, but it reveals something deeper: a way of seeing. Or rather, not seeing.

When we hear “art,” our minds rush to what we think we know – paintings, galleries, something soft or unserious. But that’s the perceptual twitch. The reflex that says: this doesn’t belong here.

And that’s precisely the problem. When we rely only on what we know, we stop noticing what might be possible. We stop seeing new value. And in doing so, we miss the deeper intelligence that artists like Asawa – and leaders like Steve Jobs – were training all along.

That twitch, that retreat from uncertainty, is the enemy of originality.

The more senior we are, the more prone we are to that reflex. It’s why leaders who create real breakthroughs often develop techniques to suspend their knowing. They look longer. Ask more questions. Invite contradiction.

The way I see Albers’ recommendation to “draw what you see” is an invitation to think about our vision. You are all familiar with “Bicycle of the mind,” Steve Jobs said about computers. But in 1981, when he said that, computers were clunky and technical. But he saw them not as tools for engineers, but as enablers of imagination. He didn’t describe what they were. He envisioned what they could become.

He drew what he saw.

There’s an important lesson to draw from this: technological excellence won’t serve you if you get the human story wrong. Jobs got many things wrong about the technology – but he got the human vision right.

What the Hand Knows

Asawa’s wire sculptures started as drawings that refused to stay flat. She’d sketch a line, then find herself pulling it into space. The wire wanted to loop, to hang, to cast shadows. Her hand was drawing something her mind hadn’t yet imagined.

This is how vision often begins – not with grand insights, but with small rebellions against the expected line.

You start sketching the way things are supposed to work, then something pulls you elsewhere. Snap camera-first interface when everyone expects menus. The disappearing photo when everyone builds for permanence. The computer as creative tool when everyone sees calculation.

Jobs didn’t sit down and think “I’ll revolutionize computing.” He was drawing toward something he felt but couldn’t yet name – this sense that technology could amplify human creativity rather than replace it. Each product was another line in a larger sketch only he could see.

Like many of us, I find myself drawing around AI and wondering: are we sketching the wrong picture? We’re drawing AI as the artist and us as the audience. But what if the lines want to go the other way? What if AI becomes the brush, and we remain the hand that holds it?

I don’t know if these lines will lead anywhere. But that’s the discipline Albers was teaching – to keep drawing what you see, especially when you can’t yet see where the drawing is going.

The Discipline of Vision

Ruth Asawa’s meander drawings, which I saw in SFMoma that day, made me realize they were lessons in staying open.

Repetitive, meditative, and precise. Each line was a practice in not knowing what the next line would bring.

This is what Albers was really teaching: that growth lives in the gap between what we know and what we see. That the moment we think we’ve figured it out, we stop growing. That vision isn’t about having the answer – it’s about maintaining the capacity to be surprised by what emerges.

“Draw what you see, not what you know” is a mindset that keeps possibilities alive. It’s the difference between leaders who repeat what worked before and those who create what hasn’t existed yet. It’s the difference between solving today’s problems and sensing tomorrow’s opportunities.

In 1940, Josef Albers wrote that “the meaning of art is: Learn to see and to feel life; that is, cultivate imagination.” Vision, in business as in art, is choosing growth over certainty, possibility over proof.

What do you see that others don’t? What are you willing to draw before you know where it leads?

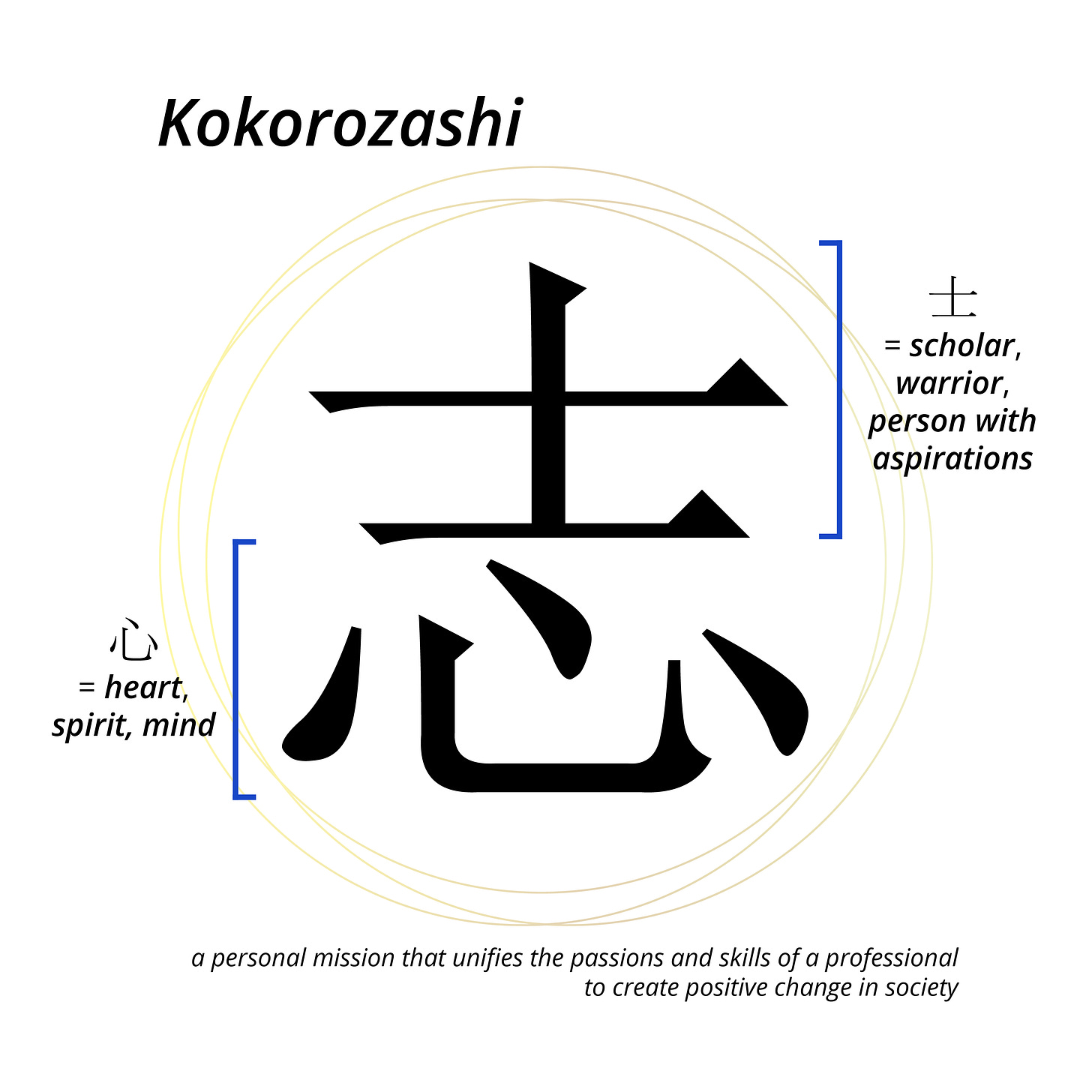

On Monday, August 19, at 8:00 PM (ET) / 5:00 PM (PT), I’ll be joining the Kokorozashi Online Seminar hosted by Globis Business School — a conversation on What Art Can Do in Business.

“Kokorozashi” (志) is a Japanese concept that means living with purpose and ambition while creating positive change. I’ll be speaking alongside artist–entrepreneur Sonal Soveni, founder of The Table & Gallery.

Helping leaders draw what they see is a topic I speak about. Curious what that could look like in your organization? Let’s talk.

If you’re enjoying Business Artistry, consider sharing it with a friend or colleague. Just hit the button below.

And as always—I’d love to hear from you. Feedback, ideas, questions, critiques: I read every note.

Just a heads-up: Some links might be Amazon affiliate links.