Moonshot or Spaceshot? How to Navigate the Two Modes of Innovation

If you've spent time in San Francisco during the summer, you know the mornings: crisp, a little chilly, but bathed in sunlight. Two weeks ago, on one of those mornings at the Ferry Building, I was sitting outside with my friend—the artist and pioneer—Michael Naimark. Coffee in hand, sunlight glinting off the bay, he turned to me and asked a question wrapped in a metaphor:

"Do you want to go to the moon, or do you want to go boldly where no one has been before—as Captain Kirk once said?"

I smiled. I’ve been following Michael’s work for years—and in recent years, through ongoing conversations. He’s one of the true pioneers of VR and AR; his Aspen Movie Map anticipated Google Street View by nearly three decades. His early experiments with living room projections—and even projecting onto objects, faces, and eyes—were precursors to today’s large-scale projection mapping. When it comes to that world, Michael is the real deal.

What I admire most is that he hasn’t slowed down. Today, he’s developing an immersive teleconferencing project at NYU Shanghai, designing a novel VR field camera, and hustling several new creative ideas. “Always,” he said with a smile. Every time we talk, I walk away with a masterclass in innovation and creative thinking.

But in that moment, sitting near Gandhi's statue, he wasn't talking about technology. He was drawing a visual map of innovation itself.

At first, I was confused. What exactly did he mean? But then the metaphor clicked: he was inviting me to reflect on how we imagine our journey through the innovation space.

I wondered if we are even aware of this distinction in the business world. Have you ever felt that tension—between driving toward a specific result and staying open to the unknown?

Moonshot or Spaceshot?

“Space: the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Its five-year mission: to explore strange new worlds; to seek out new life and new civilizations; to boldly go where no man has gone before!”

Captain James T. Kirk

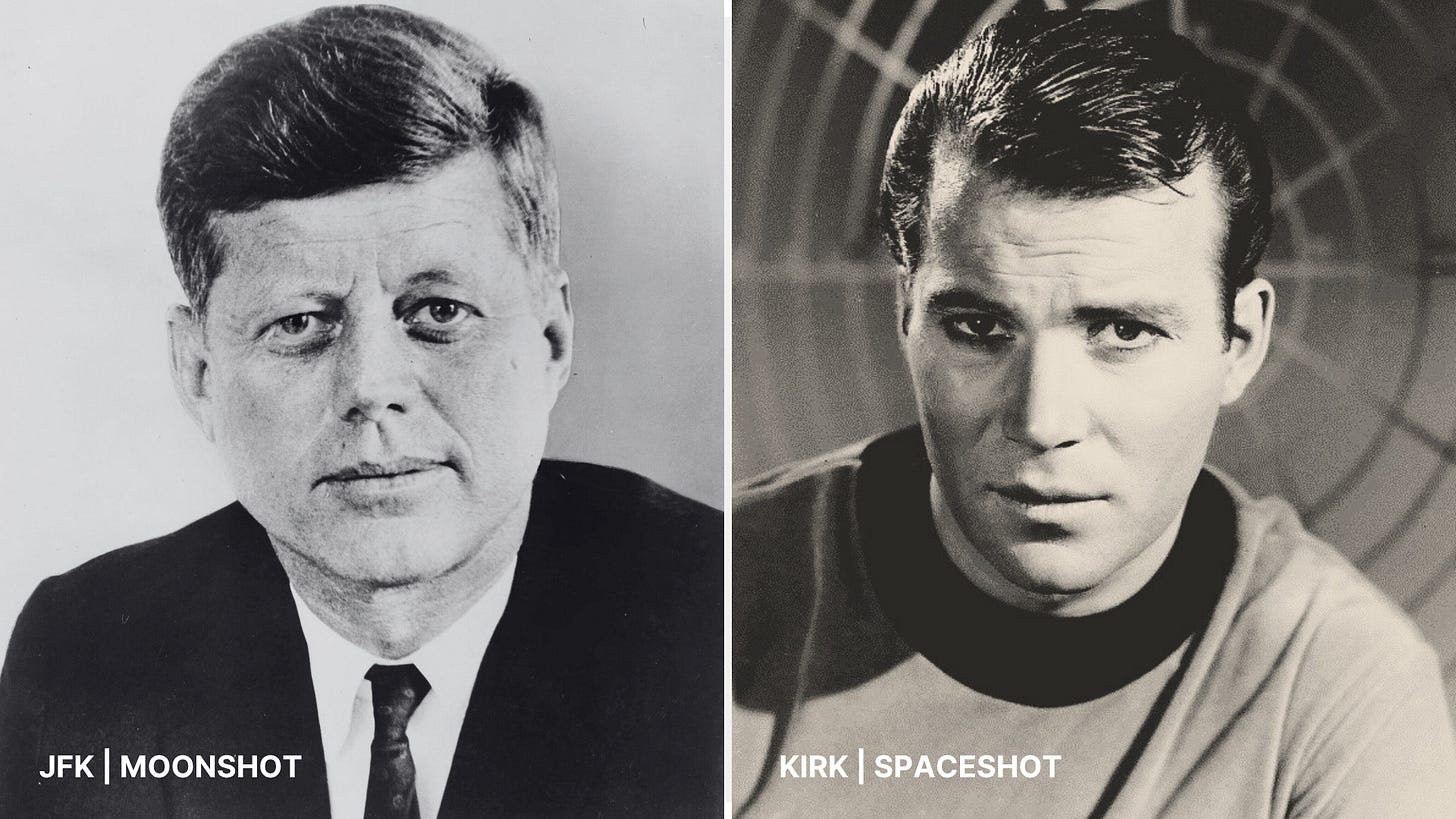

Innovation is a word we toss around freely, but we rarely stop to define what kind we're actually after. Michael's metaphor helps. It splits the pursuit into two essential modes: Moonshot and Spaceshot.

If the Moonshot takes its name from President John F. Kennedy's 1962 declaration—"We're going to the moon"—then it represents a clear, specific destination. The path may be complex, but success is measurable. You know exactly where you're headed, even if you don't yet know how to get there.

By contrast, the Spaceshot draws its spirit from Star Trek's iconic mission: "To boldly go where no one has gone before." This is directional exploration. You're venturing into the unknown without a fixed endpoint. You don't know what you'll discover—or where you'll end up—but you go because curiosity compels you.'

The key difference:

Moonshot = Known destination, unknown path

Spaceshot = Unknown destination, unknown path

Both require innovation and risk-taking, but they come with different mindsets and success metrics. A moonshot succeeds when you reach the specific goal. A spaceshot succeeds when you discover something valuable—even if it's not what you expected.

The Innovation Spectrum in Practice

Some industries lean naturally toward one mode. The pharmaceutical industry, for instance, runs almost entirely on moonshots—specific diseases to cure, specific molecules to develop. But the most breakthrough drugs often come from spaceshot-style basic science: researchers following strange proteins or unexpected cellular behaviors, not business plans. One mode chases a target; the other follows a question.

The same was true at Pixar. Under Ed Catmull and John Lasseter, they had a clear goal: make the first fully computer-animated feature film. Toy Story was a moonshot. But the R&D required—new software, storytelling forms, rendering techniques—came out of years of open-ended exploration inside Lucasfilm. The moonshot only succeeded because a spaceshot came first.

That's the deeper truth: moonshots and spaceshots aren't opposing philosophies. They're complementary modes. Innovation leaders don't need to choose one—they need to recognize which mode they're in, and why. Confusing the two causes misalignment. Naming them clearly sets teams free to think accordingly.

If this sounds like a contradiction—it's not. The real danger isn't using both modes; it's pretending you're in one while managing like the other.

The Twitch of Doubt

In corporate innovation labs or startup pitches, you'll often hear phrases like "we're building a moonshot." But when you dig deeper, the plans are meticulously plotted. The destination is known. The risk is pre-managed.

That's not a moonshot. That's a mission.

Worse, sometimes teams believe they're exploring space—prototyping, researching, immersing themselves in user behaviors—when leadership is secretly waiting for a business case. By doing so, the leadership set the teams to orbit the known, rather than truly exploring the unknown.

That tension shows up as a twitch: the sudden pressure to justify a prototype too early. The request to prove ROI before the idea has a shape. The pivot toward the familiar because ambiguity feels expensive.

We say we want exploration, but we fund missions. We say we want moonshots, but we manage like it's a shuttle launch.

This confusion might kill innovation before it starts. Teams waste energy pretending to explore while actually executing. Or they commit to destinations they don't actually believe in because it sounds more fundable than "we want to see what's possible."

Choose Your Map—And Stick to It

One of the biggest favors a leader can do for their team is to clearly name the mode they're in. Not just to align expectations - but to preserve trust.

In our client workshops at The Artian, we've seen how this clarity changes behavior:

When teams know they're on a mission, they make decisions faster. The constraints fuel focus.

When they're pursuing a moonshot, they build with higher stakes in mind. They accept that failure is likely but worthwhile.

When they're given space for a spaceshot, they ask better questions. They make weirder connections. They tolerate the fog.

But here's what we've learned: most organizations need both modes running simultaneously. The mistake isn't choosing the wrong mode—it's mixing them up or switching between them without warning.

The companies that consistently innovate have learned to run parallel tracks: moonshot teams with clear objectives and measurable milestones, working alongside spaceshot teams given permission to wander and discover. 3M's famous "15% time" produces spacehot discoveries that later become moonshot development programs. Bell Labs operated this way for decades, funding both directed research (moonshots) and pure research (spaceshots) under the same roof.

The key is knowing which conversation you're having. When your team walks into a room, they should know whether you're asking them to solve a known problem or discover an unknown opportunity.

The Mode Test: Ask your team to describe success in their current project. If they start with metrics and timelines, you're in moonshot territory. If they start with questions and possibilities, you're running a spaceshot.

Because the moment you confuse exploration for execution—or ask explorers to justify their wandering—you've lost both the moon and the stars.

Helping teams understand modes of innovation is what I speak about. In my keynotes, I show leaders how to think about innovation. Curious what that could look like in your organization? Let’s talk.

If you’re enjoying Business Artistry, consider sharing it with a friend or colleague. Just hit the button below.

And as always—I’d love to hear from you. Feedback, ideas, questions, critiques: I read every note.

Just a heads-up: Some links might be Amazon affiliate links.